Mavica .411 converter

I bought a Sony Mavica MVC-FD85 a while back. It is an analog still camera, with the storage medium being a floppy disk. The intended goal was to have a universal medium which could easily be transported to a computer, with use cases such as online stores, emails and rudimentary video capture. At the best quality, 6 images fit onto a single HD-floppy. Later models used mini-CDs and could store more. Amazing device, great party trick. The aggressive JPEG compression adds a great nostalgic retro tone to photos, whilst still keeping the (relative) convenience of digital cameras. Readout works great if you have a USB floppy drive; excellent reason to build a floppy drive into my next gaming PC. This works on Android phones too by using a USB-C to USB-A dongle.

Two weeks ago, my dear FD85 crumbled to dust in my hands. I disassembled it and figured out that the CCD in the camera is probably dead. Even though my camera will likely never capture again, I really appreciate the ease of disassembly. The CCD could be taken out with just two screws and a ribbon cable. After my despair had settled a bit, I started to fiddle with the files generated on the floppies. With this, I dove into a rabbit hole as deep as a dinner plate, but I wanted to share my little investigation here.

Example image. Not taken with my FD85, sadly.

Aside from the .JPG images which can be directly opened an manipulated, an .HTML file disguised as an .HTM file is generated which is likely for internal housekeeping and monitoring the metadata of the pictures taken. It can be opened with any browser which successfully formats the file.

There is something else present, though. These are the .411 files, which are the thumbnails for when you scroll through the camera and want an overview of the images present on the disk. Since I like the ingenuity of programmers to fit as much data in as little space possible, I wanted to view the thumbnails directly. Turns out, you can’t. At least, not directly. After searching “.411 file format”, you get a few results pertaining to the opening of the files with software from some highly SEOed sites. Since I dislike downloading malware, I went to look for a suitable alternative. There wasn’t.

I did find two important sources for my further research: a short Archiveteam Wiki entry of the Sony Mavica .411 file and two documentation files on the 411 compression directly from the Linux Kernel: 411P and Y41P.

Here, .411 will refer to files, whilst 411 will refer to the compression technique.

Python adventures

Python to the rescue: I wrote a script to read the .411 file. Taking the raw byte stream and putting it into an array was easy enough, but now came the issue of byte packing (where your relevant data lives in a file). Some assumptions that were also clear is that the .411 file is always exactly 4608 bytes long, with the resulting thumbnail being 64 by 48 pixels. Since it is a RAW file, no metadata is included and every byte contributes to the image. The issue is that for 411 subsampling, 2/3rds of the file is dedicated to luminance whilst the remaining 1/3rd is color information. Having written a function that subdivides the data into two arrays according to the 411P packing, the resulting luminance image turned out to look like this:

Luminance of the 411P decompression

Luminance of the 411P decompression

Hm. Something doesn’t check out. Wrong format, probably. Let’s give Y41P a shot, surely I just messed up and this is the correct format?

Luminance of the Y41P decompression

Luminance of the Y41P decompression

Nope. Ok, what now? Time to open the hex editor.

1

2

3

00000000: 09 2A 55 04 60 9F 05 05 06 07 82 82 07 06 07 06

00000010: 82 82 07 05 08 0B 81 83 0B 0D 0E 0F 82 82 0D 0E

00000020: 0A 0C 80 83 0D 0F 11 11 83 82 11 14 19 22 85 7F

No structure to be detected here. However, if you switch the data visualizer to decimal unsigned, you get the following:

1

2

3

00000000: 9 42 85 4 96 159 5 5 6 7 130 130 7 6 7 6

00000010: 130 130 7 5 8 11 129 131 11 13 14 15 130 130 13 14

00000020: 10 12 128 131 13 15 17 17 131 130 17 20 25 34 133 127

Apparently, ImHex does not allow the visualized bytes to be copied. Copying the bytes as a python list, the string was generated with

' '.join([f"{x}".rjust(3, ' ') for x in data]).

Aha! Interesting. If we rearrange the bytes in pairs of six, the data starts to make sense.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

00000000: 9 42 85 4 96 159

00000006: 5 5 6 7 130 130

0000000C: 7 6 7 6 130 130

00000012: 7 5 8 11 129 131

00000018: 11 13 14 15 130 130

0000001E: 13 14 10 12 128 131

00000024: 13 15 17 17 131 130

0000002A: 17 20 25 34 133 127

Since the 0th to the 3rd byte are consistently of a lower value, with bytes 4 and 5 a higher one, the byte order is deciphered. This makes sense, since the luminance Y will likely be a generally low value for a darker picture, but the U and V values will be around 127 (255//2) for images with muted, gray or “natural” colors. Finally, we can extract by rearranging the raw byte stream in groups of 6 and creating the Y, Cb and Cr arrays.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

def mavica_411_to_yuv_arrays(fp):

...

npimg = npimg.reshape((chunks,chunksize))

for i,v in enumerate(npimg):

#print(v)

Y[i*4:(i+1)*4] = [v[0],v[1],v[2],v[3]]*1

Cb[i*4:(i+1)*4] = [v[4]]*4 # here's the 411 subsampling

Cr[i*4:(i+1)*4] = [v[5]]*4

YCbCr[i*12:(i+1)*12] = [v[0],v[4],v[5],

v[1],v[4],v[5],

v[2],v[4],v[5],

v[3],v[4],v[5],]

...

YCbCr = YCbCr.reshape((48,64,3))

...

The final realization is the 4-fold duplication of the Cb and Cr bytes. I think it is great that the color, which we generally consider to be very important, is the component that can be easily lossy encoded. Behind the scenes, some more processing happens, but this is how one may read out a .411 file.

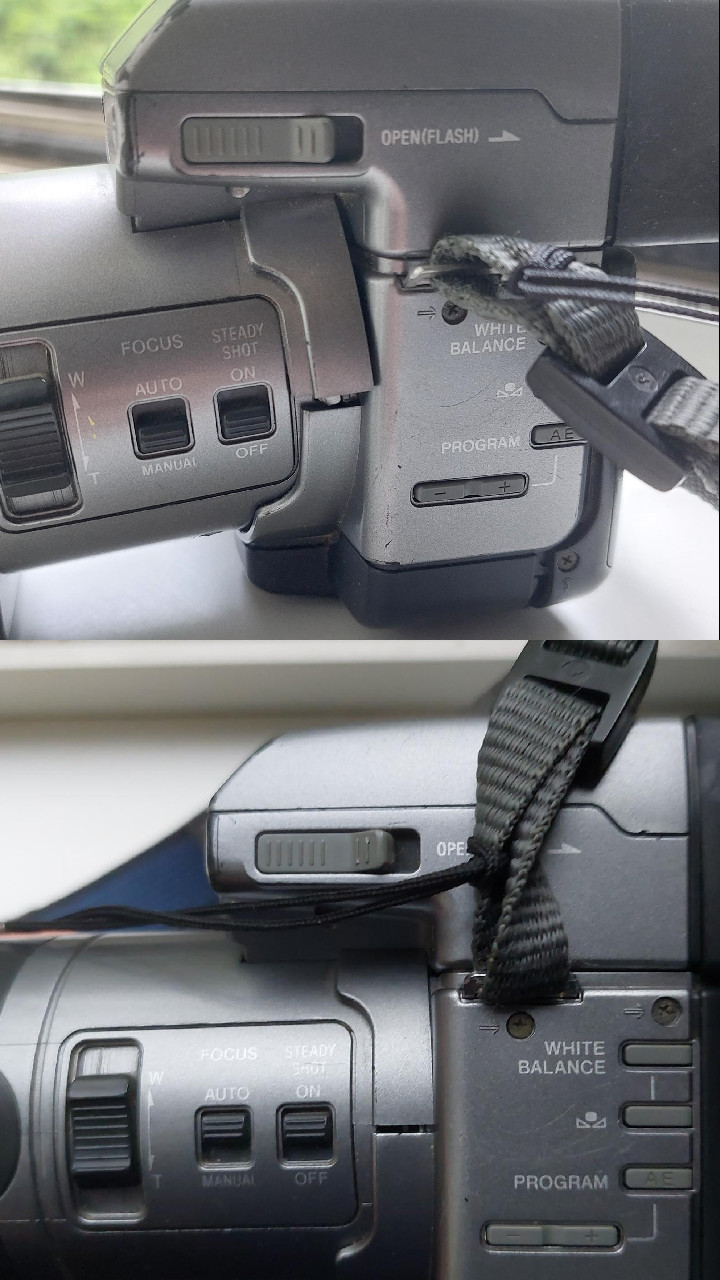

The final thumbnail. Click to zoom - looks just a bit better that way.

The final thumbnail. Click to zoom - looks just a bit better that way.

Another library and final thoughts

Everything is packed together in a small script to experiment with. You can find it here on my Gitlab. By employing the functions directly, you can mess with the encoding or the color conversion which is also fun to do. Running the script in shell will result in any .411 files being converted to the png format.

For some reason, I keep messing with weird file formats and trying to open them. I hope that this this could be of insight to someone - maybe I’ll repost it somewhere found more easily. Of course, this is entry-level image processing, but especially now, I am trying to keep my remaining gray matter somewhat stable. Fun times.

I am looking for some new Mavica cameras, I really like the things. I just received an FD91 - completely tortured and mangled by DHL. Thanks. (Lately, a lot of devices have been failing around me. Sort of a reverse King Midas I figure.) The lens assembly was crooked, the bottom smashed and the screen absolutely obliterated. The virtual viewfinder still works though! After a disassembly which was significantly harder than the FD85, I removed some loose plastic and by applying some - uh - camera chiropractic on it, I was able to bend the lens assembly properly perpendicular to the main assembly and the shell around the reader, so I’ve got that going for it.

Before and after some of the damage. Man, these things are like Nokias.

Before and after some of the damage. Man, these things are like Nokias.

Expect some posts regarding the Mavica systems.